news

Vaccine-Delivery Patch with Dissolving Microneedles Boosts Protection

Primary tabs

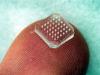

A new vaccine-delivery patch based on hundreds of microscopic needles that dissolve into the skin could allow persons without medical training to painlessly administer vaccines -- while providing improved immunization against diseases such as influenza.

Patches containing micron-scale needles that carry vaccine with them as they dissolve into the skin could simplify immunization programs by eliminating the use of hypodermic needles -- and their "sharps" disposal and re-use concerns. Applied easily to the skin, the microneedle patches could allow self-administration of vaccine during pandemics and simplify large-scale immunization programs in developing nations.

Details of the dissolving microneedle patches and immunization benefits observed in experimental mice were reported July 18th in the advance online publication of the journal Nature Medicine. Conducted by researchers from Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology, the study is believed to be the first to evaluate the immunization benefits of dissolving microneedles. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"In this study, we have shown that a dissolving microneedle patch can vaccinate against influenza at least as well, and probably better than, a traditional hypodermic needle," said Mark Prausnitz, a professor in the Georgia Tech School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

Just 650 microns in length and assembled into an array of 100 needles for the mouse study, the dissolving microneedles penetrate the outer layers of skin. Beyond their other advantages, the dissolving microneedles appear to provide improved immunity to influenza when compared to vaccination with hypodermic needles.

"The skin is a particularly attractive site for immunization because it contains an abundance of the types of cells that are important in generating immune responses to vaccines," said Richard Compans, professor of microbiology and immunology at Emory University School of Medicine.

In the study, one group of mice received the influenza vaccine using traditional hypodermic needles injecting into muscle; another group received the vaccine through dissolving microneedles applied to the skin, while a control group had microneedle patches containing no vaccine applied to their skin. When infected with influenza virus 30 days later, both groups that had received the vaccine remained healthy while mice in the control group contracted the disease and died.

Three months after vaccination, the researchers also exposed a different group of immunized mice to flu virus and found that animals vaccinated with microneedles appeared to have a better "recall" response to the virus and thus were able to clear the virus from their lungs more effectively than those that received vaccine with hypodermic needles.

"Another advantage of these microneedles is that the vaccine is present as a dry formulation, which will enhance its stability during distribution and storage," said Ioanna Skountzou, an Emory University assistant professor.

Pressed into the skin, the microneedles quickly dissolve in bodily fluids, leaving only the water-soluble backing. The backing can be discarded because it no longer contains any sharps.

"We envision people getting the patch in the mail or at a pharmacy and then self administering it at home," said Sean Sullivan, the study’s lead author from Georgia Tech. "Because the microneedles on the patch dissolve away into the skin, there would be no dangerous sharp needles left over."

The microneedle arrays were made from a polymer material, poly-vinyl pyrrolidone, that has been shown to be safe for use in the body. Freeze-dried vaccine was mixed with the vinyl-pyrrolidone monomer before being placed into microneedle molds and polymerized at room temperature using ultraviolet light.

In many parts of the world, poor medical infrastructure leads to the re-use of hypodermic needles, contributing to the spread of diseases such as HIV and hepatitis B. Dissolving microneedle patches would eliminate re-use while allowing vaccination to be done by personnel with minimal training.

Though the study examined only the administration of flu vaccine with the dissolving microneedles, the technique should be useful for other immunizations. If mass-produced, the microneedle patches are expected to cost about the same as conventional needle-and-syringe techniques, and may lower the overall cost of immunization programs by reducing personnel costs and waste disposal requirements, Prausnitz said.

Before dissolving microneedles can be made widely available, however, clinical studies will have to be done to assure safety and effectiveness. Other vaccine formulation techniques may also be studied, and researchers will want to better understand why vaccine delivery with dissolving microneedles has been shown to provide better protection.

Beyond those already mentioned, the study involved Jeong-Woo Lee, Vladimir Zarnitsyn, Seong-O Choi and Niren Murthy from Georgia Tech, and Dimitrios Koutsonanos and Maria del Pilar Martin from Emory University.

"The dissolving microneedle patch could open up many new doors for immunization programs by eliminating the need for trained personnel to carry out the vaccination," Prausnitz said. "This approach could make a significant impact because it could enable self-administration as well as simplify vaccination programs in schools and assisted living facilities."

Research News & Publications Office

Georgia Institute of Technology

75 Fifth Street, N.W., Suite 314

Atlanta, Georgia 30308 USA

Media Relations Contacts: John Toon, Georgia Tech (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu), Holly Korschun, Emory University (404-727-3990) (hkorsch@emory.edu) or Abby Vogel Robinson, Georgia Tech (404-385-3364) (abby@innovate.gatech.edu).

Writer: John Toon

Groups

Status

- Workflow status: Published

- Created by: John Toon

- Created: 07/17/2010

- Modified By: Fletcher Moore

- Modified: 10/07/2016

Keywords

User Data