news

Children on Medicaid May Lack Sufficient Access to Dental Care

Primary tabs

Debra McCollister has been a health hygienist with the Georgia Department of Public Health for nearly a decade. The Tennessee native loves her job, and her warm and lively personality immediately makes her young, and sometimes nervous, patients feel at ease. She cracks jokes with sullen pre-teens. “Are you married? No? Well, it’s probably best to finish school first.” To the younger children, McCollister offers small toys or stickers featuring animated characters. “I don’t know who has more fun, me or the kids,” she said with a laugh.

McCollister is always on the move. She travels to six North Georgia county health clinics every week and sees between 40 and 50 children a month. She takes x-rays, cleans teeth, and educates caregivers and children about good oral hygiene and nutritional habits. “I talk about how much sugar is in juice, that type of thing.”

Depending on the county, half to nearly all of McCollister’s patients are on Medicaid or CHIP, the Children’s Health Insurance Program. In the United States, these programs cover more than 73 million adults, children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities who can’t afford health insurance. As part of Medicaid and CHIP, states are required to provide dental benefits for kids — general maintenance of dental health and treatment of tooth decay.

It’s often difficult for low-income children to access dental care, according to McCollister and others in the oral health community. Parents or caregivers take unpaid time off of work; families travel long distances by public transportation or taxi, get rides from friends and family, and some even walk to and from their appointments. “It just breaks my heart,” McCollister said. “There are a lot of hoops and hurdles for parents to go through.”

* * *

Two recent nationwide Georgia Tech studies — the first to examine Medicaid capacity at the provider level — confirm the experiences of oral health providers and recipients of publicly-funded dental insurance: children who rely on Medicaid for dental care may not have adequate access to providers.

Nicoleta Serban, professor in the Georgia Tech School of Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISyE), compared provider and Medicaid data to state access information reported by the Health Policy Institute (HPI), a branch of the American Dental Association. HPI produces research related to the U.S. oral health care system and is considered a leading expert on the topic.

During a May 2017 webinar, HPI Chief Economist and Vice President Marko Vujicic said, “…nationwide, the majority of publicly-insured children live within 15 minutes of a Medicaid dentist, and in some states, it’s as high as 99-percent.”

Serban wanted to know more about HPI’s statistic, so she examined publicly-available provider information and Medicaid data for 43 states. The result is a more holistic view of the U.S. Medicaid program, including the most important information about dental providers, according to Serban: whether or not they’re accepting new Medicaid patients.

“Dentists dedicate a small portion of their caseload to children on Medicaid, and many dentists don’t accept new patients,” she said.

For example, HPI’s data shows that 30-percent of dentists accept Medicaid in Florida, but according to a recent survey of nearly all of the state’s licensed dentists, a limited number reported accepting new Medicaid-enrolled children.

Another factor which skews access numbers is the patient-to-provider ratio. HPI estimates, on average, one provider sees 500 children a year. Serban found, though, that less than a quarter of dentists nationwide provide care for 500 or more children on Medicaid.

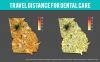

Traveling for Dental Care

A second, more in-depth study of dental care access from the Georgia Tech Health Analytics Group, co-led by Serban, looked at distance — how far children on Medicaid and their families travel to receive dental care.

Amanda Black’s children – 11 and 4-years-old – have received Medicaid benefits their entire lives. The family lives in rural Union County, and twice a year, Black drives two hours round trip to the closest dental provider at the Gilmer County Health Department where her kids receive regular dental check-ups and cleanings. The single mother takes unpaid time off of work from her job as a home health aide.

“When you lose income, it's for the whole household,” Black said. “When you live in a small town, it’s almost like you’re being punished. People in big cities don’t have to travel; what’d we do wrong?”

Families like Black’s aren’t uncommon. Serban estimates in Georgia, 23-percent of Medicaid-eligible children exceed state standards for travel distance — 30 miles for urban communities and 45 miles for rural.

“Needless to say, 30 to 45 miles of travel means missing a whole school day and hours of time off from work,” she said. Meanwhile, families that pay out of pocket for dental care or have private insurance experience shorter travel distances.

Serban and her research team examined data from 39 states and also found that the number of Medicaid-enrolled children per dentist varied by location and the type of provider. Urban and suburban communities have higher numbers than rural areas (which may be driven by demand), while pediatric dentists often see more patients than general dentists. Specialists generally treat few children on Medicaid. Overall, dentists see fewer patients than the minimum caseload amount outlined by HPI.

* * *

Estimating access is more than a matter of data, noted Serban and Scott Tomar, a study co-author, and professor in the University of Florida’s College of Dentistry. HPI presents its estimates to state health policy committees, which control the Medicaid program at the state level.

“In my state of Florida, testimony has been given before the state legislature to oppose other proposed workforce models. The HPI data was used as justification to deny funding for dental therapists,” said Tomar, who is also a consultant with the American Dental Association.

“The takeaway message is, there’s not really a problem with access.” He continued, “Families are getting hurt when the HPI information is used to stave off other programs and other models that might be effective in increasing access to care.”

Without access to preventive care, dental issues like tooth decay can worsen and require emergency care. Over 212-thousand children in the U.S. had dental emergency visits in 2012; more than two-thirds were covered by Medicaid.

HPI's Response

During presentations to Medicaid policymakers, HPI’s Marko Vujicic acknowledges that HPI’s data shows approximately where enrolled providers are located relative to Medicaid patients, but not whether they’re accepting new patients. He said determining the level of Medicaid access is a complex issue. “There is no gold standard way of measuring access.”

In a statement provided to the Institute for People and Technology (IPaT), HPI congratulated Serban and Tomar on their study published in the Journal of Public Health Dentistry, and said it enhanced its own findings:

We applaud these authors’ efforts to build on our analysis and advance the policy discussion in Florida and Georgia. The Health Policy Institute is currently collaborating with government agencies in several states on a much more refined analysis of access to and utilization of dental care services among publicly insured children and adults, based on detailed administrative and claims data as well as innovative primary data we are helping to collect. We will continue to help advance this important area of health policy research, including collaborating with outside researchers, and welcome additional feedback on our work as it evolves.

(Read the Health Policy Institute's full statement)

Serban said her studies also have limitations; providers don’t always file claims or have missing or inactive identification numbers. She said, though, that these findings can help states begin to gauge the level of dental care provided to Medicaid-insured children.

In September 2018, Serban and Tomar received a $1.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue researching access to preventive dental care for children. IPaT, the School of Industrial and Systems Engineering, and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta have previously provided funding for this research. IPaT also provides access to multiple years of Medicaid data to support a deeper understanding of the challenges and patterns surrounding healthcare access.

Graphics by: Raul Perez

Groups

Status

- Workflow status: Published

- Created by: Alyson Key

- Created: 07/11/2019

- Modified By: Alyson Key

- Modified: 07/11/2019

Categories

User Data